Episode transcript The transcript is generated automatically by Podscribe, Sonix, Otter and other electronic transcription services.

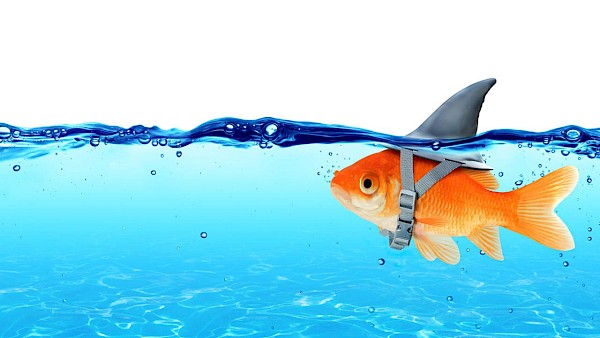

Hi everyone. Welcome to the 5 Minutes Podcast. Today, I like to talk about one thing that many times mislead people in terms of risk management. One of the very common things we do when we are analyzing risks is to calculate what is called EMV, or the expected monetary value of a risk. It's a very simple calculation. You take the probability and multiply it by the impact. Let me give you an example. Let's suppose you have a risk that has a 10% probability of losing $1,000. 10% of $1,000 gives you an exposure of $100. Simple like that. If you have a project with, for example, two risks just to be very simple, what people usually do they take 20%, for example. The second risk has a probability of 20% of 1000, the same amount of impact. So 20% of 1000 is 200. If you add the 100 that I just said for risk one, you have an exposure of 300. Many people use this exposure to calculate the reserves, the amount of financial reserves you need to have to protect yourself against the risk. But what is the problem? This concept of using EMV as a reserve to protect your full set of risks is only valid if you have a lot of risks. A lot. It's the same case for an insurance company. Why? For you? You cannot afford to lose your car, but the insurance company can afford to lose your car.

For example, for an accident or to be stolen. Why? Because the insurance company has many, many cars in its portfolio. It's like you have many, many risks. If you have only two and you do a protection of 300, what happens if risk one happens? You lose 1000. If risk two happens, you lose a thousand. So, with the 300, you cannot even afford to have one of the two risks to happen. So every time you use EMV to dimension your reserves, it's only worth it if you have a portfolio of projects and if you have hundreds and hundreds of risks because then you will work with an assumption that some risks will not occur, and the amount of reserve you put for them will protect the full context. It's like, for example, if you have your car stolen, it's your car, it's your only car. It means you want to have full protection. But for the insurance company, your car will be paid. For example, if it's stolen by someone else who paid the premium of the insurance without having the car stolen. If, for example, the insurance company has 10,000 cars in its portfolio and all of them are stolen, the insurance company will go bankrupt. Because they bat at different odds than you because they dilute their risks. If you have only two, three, four, or five risks in your project, you cannot use EMV because EMV will not be reliable for you doing that.

So then, what can you do? It depends on your risk tolerance. Most of the time, people use more extreme cases like worst-case scenarios and best-case scenarios. If you are more conservative, you tend toward using the worst-case scenario. For example, you will have, for example, a thousand reserves that will protect you against one of the risks fully. So, this is a more conservative approach. If you are towards a more aggressive approach, you will imagine that only the opportunities will happen and no risks will happen. Then, you will not only have any reserves, but you will probably even reduce your budget because you expect to have opportunities for savings. Did you see these two different cases? And it depends on who your company is, who you are, the size of your portfolio, and the size of risks that you are on stage. For example, if you are a capital project, for example, doing a nuclear power plant, I watched that series, the days about the Fukushima disaster in Japan. So, if you have a nuclear power plant. You cannot afford the impact. I'm not even talking about human life. Okay, let me put this out of the game here. Just financially. If a disaster occurs, the damage is sometimes far and far bigger than all the investments in Fukushima.

I'm pretty sure that the decommissioning of Fukushima will probably cost dozens of times more than the construction of the power plant. Why? When a catastrophic disaster like this one, or a black swan event, happens, the size of the damage and the size of the impact is unbearable. It's unbearable. There is no way you can build reserves on that because you cannot say, oh, I'm building a nuclear power plant. Oh, how much is the cost of the nuclear power plant? Oh, it's $3 billion. Okay, then I need a reserve of $1 trillion. There is no way you can do that. This is why, for example, most of the very complex projects with a huge amount of risk at stake are usually funded by governments. They are usually funded by extremely large organizations because they are the only ones who can afford that damage. And it's not just by calculating. Emv and multiply probability times the impact of your 3 or 4 risks in your project that you are protecting your project. Don't be misled to think like that. It's not so simple. It depends much more on how is your behavior towards accepting or not accepting the risk. Think about that, and see you next week with another 5 Minutes Podcast.